Keiichi

Tanaami

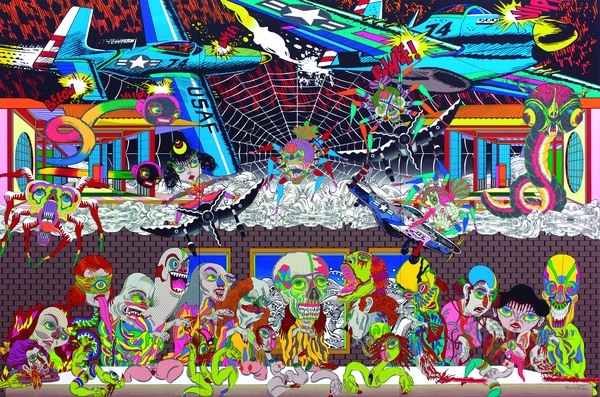

Keiichi Tanaami’s childhood was marked by the chaos brought about by the Second World War. He was only nine during the Tokyo Air Raid of 1945 and his family relocated from their Tokyo home to Meguro, a suburban residential district, from where he observed over a hundred firebombing attacks on his native city. Images of roaring American airplanes, searchlights, bombs and fleeing masses were deeply lodged in his memory, later becoming his core iconography – a blur of his nightmares and real memories. Other childhood influences included kamishibai – children’s picture card shows performed on the streets of war-torn Tokyo – as well as Tanaami’s obsessive daily cinema visits, where he was particularly drawn to popular monster movies starring glamorous actresses, who also later became motifs in his work. A talented draughtsman, Tanaami graduated in graphic design from the Musashino Art University in 1960. He quickly forged a successful career in design and advertising, illustrating the Japanese releases of record covers for Jefferson Airplane and The Monkees, among other projects. An encounter with the Japanese neo-dada scene centred around the studio of the artist Ushio Shinohara, as well as Manga-style cartoons, inspired Tanaami’s foray into art. His colourful, overpopulated psychedelic collages, animations and drawings frequently juxtapose war imagery with American and Japanese pop culture, communicating the underlying peace message.

Keiichi Tanaami’s first trip to New York in the late 1960s introduced him to the work of Andy Warhol, whose interdisciplinary approach constantly shifting between art and advertising echoed Tanaami’s own path. He would later visit Warhol’s Factory, as the first art director of the Japanese edition of Playboy magazine. From 1965, Tanaami began to work with video and animation in collaboration with Yoji Kuri’s Experimental Animation School. Commercial War 1971 takes the emblems associated with American consumer society – like Coca-Cola – and juxtaposes them with Tanaami’s own visual vocabulary. The effect is a comic-strip-like critical take on the advent and impact of American consumer culture on foreign nations. Also commenting on the American invasion of Japan both in military and cultural terms is Crayon Angel from 1975. Opening with the sound of sirens and dramatic drumming over images of fighter jets and explosions, the fast-paced video goes on to combine black and white photographs of Japanese families and children, often seen through black prison-like bars which recall Japanese fusuma (sliding doors used to partition spaces within a room), with psychedelic characters and superheroes appearing on traditional Japanese patterns. The incongruity of such imagery points to Japan’s difficult past, its growing consumerism and the pervasive nature of global pop culture.